If the mash pH is too high, you can extract tannins and bad flavors from your mash. Reduces chill haze in the finished beer.Better flocculation of proteins during the cold break and after fermentation is complete.Fights bacteria growth during fermentation.Helps convert starches to sugars (improving mash efficiency).Your mash pH should be between 5.2 and 5.6-yes, just a little acidic. Knowing your starting pH is important if you practice all-grain brewing. When you cry, your eyes don’t burn because they are perfectly pH balanced. The best example of neutral pH is your tears. Baking soda is basic and has a pH of about 9. Lemon juice is acidic and has a pH of around 2. It’s measured on a scale from 1 to 14, with 7 being neutral.

The measurement of your water’s acidity or basicity is its pH. Whether you have it professionally tested, or use a test kit to do it yourself, you want to be on the lookout for certain ions and minerals in the water. But to be honest, I recommend getting it professionally checked and contacting your local water municipality first. You can buy a home water test kit specifically for brewing from LaMotte. Test The Water Yourself with a Brewing Test Kit In about a week, you’ll receive a water report like the one below.ģ. The cost of the kit also covers the shipping.

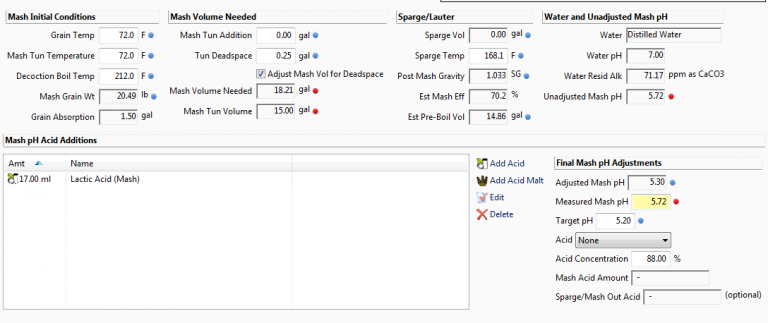

Then, collect the sample and ship it back to the lab for analysis. You run your tap water from the source where you’ll actually get your brewing water for about five minutes. For about $30, they’ll send you a test kit that includes a water sample bottle. Send a sample of your water to a company like Ward Labs. That’s why I recommend also getting you water tested. Just remember that reservoirs can change and the chemistry can change as it travels through to your home. This is especially true if you have a lot of craft beer brewers in your town.Ībove is an example of a water quality report I was emailed every week from the city of Boulder, Colorado. Some places even have special reports for brewing water they’ll email you on a regular basis. Let them know you’re using the water for homebrewing. Get a Water Report From Your Local Municipal Water SourceĬontact your local water treatment facility, and ask for the most recent water report. However, if you plan on using tap water, you have three options to learn the mineral profile. Spring water contains minerals, just like tap water, so if you want to build a water profile, you’ll have to contact the bottler to learn the existing mineral content. If you’re working with this type of water, you can skip down to adding brewing salts. It contains no minerals so you can build your water profile from scratch. Distilled water or RO (reverse osmosis) water: This is water stripped of all minerals resulting in pure H2O.ĭistilled or RO water is like working with a blank sheet of paper.Spring or bottled water: This is water you can buy at the grocery store and contains a base amount of minerals.Tap water (municipal water): This is the water in your home and contains a base amount of minerals from your local water reservoir.There are three main water sources you can choose from: The first thing you need to do before you start messing with salt additions is to get a base mineral profile of the water you’ll use for your beer. It’s up to you! What’s Your Brewing Water Source? The ins and outs of the brewing water can be simplified to allow you to experiment with your own finished beers. Ironically, this seemingly simple natural element is the most complex. Just ask the guys from Brülosophy! They’ve been running experiments and determined that water chemistry really matters.Īnd let’s face it, beer is 90% to 95% water. Maybe this is a BeerSmith question, but I figured I'd toss it out here and see if anyone found a way to get these numbers closer - I hate having to use multiple tools.Brewing water chemistry significantly impacts your beer’s flavor and mouthfeel. However, BS2 knows how big the GF's capacity is (set at 29.9L in the included addon), so one would think it should be able to include that as part of the calculation. The GF numbers add up to much smaller total volumes than the BeerSmith numbers do, so perhaps that's the source of the problem. What I haven't been able to get is the difference between the Grainfather sparge calculator and the BeerSmith sparge calculator. For myself, I was able to follow some recommendations (like setting deadspace to 0) to get very close between predicted and actual. I also have seen several profiles floating around with varying levels of accuracy. I know that BeerSmith2 has a Grainfather equipment profile plugin.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)